As athletes, our muscles and body are under constant fatigue and stress from the high-intensity, functional movements we demand of them. To stay at peak performance, the foundations never change: eat a whole-food diet, sleep well, take rest days, and stay hydrated.

Yet, even with these habits dialed in, certain supplements—backed by decades of research—can give you an extra edge, helping you recover quicker, train harder, and support long-term health.

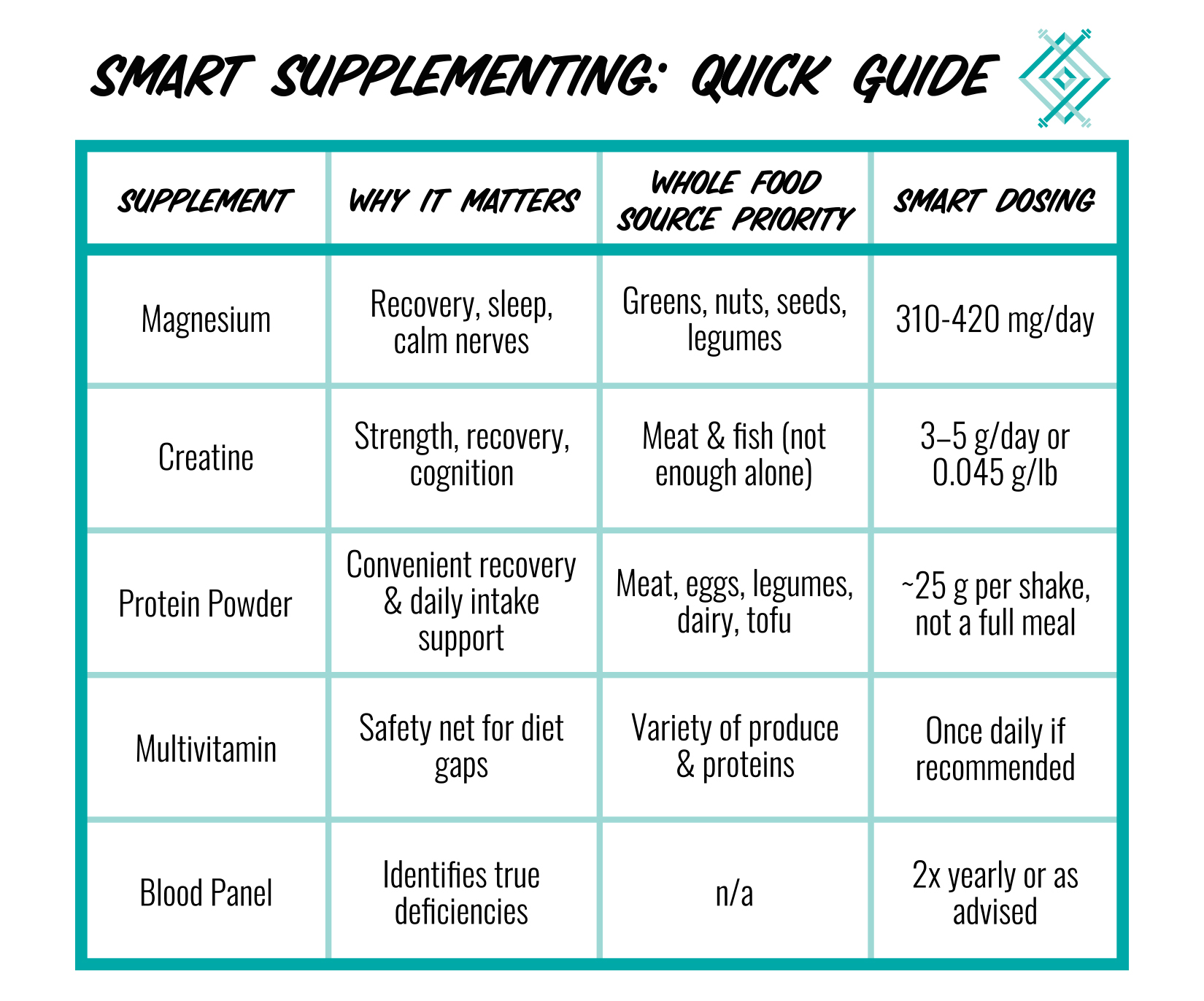

In this article, we’ll cover three proven supplements—magnesium, creatine, and protein powder

Before we dive into the research, we strongly encourage you to get a blood panel twice a year. Blood work reveals deficiencies you may not feel day-to-day. The most common deficiencies may include:

Think of blood work as a blueprint for your health, helping you know when to tweak your diet or support it with smart supplementation.

Magnesium supports over 300 enzymatic reactions, including muscle contraction, nerve signaling, energy production, and sleep regulation. [4]

Creatine is one of the most researched sports supplements and helps regenerate ATP (adenosine triphosphate)—the molecule your muscles use for energy during contractions. [8] When ATP is used for energy, it becomes ADP (adenosine diphosphate). Your body then has three systems to recycle ADP back into ATP: the phosphagen system (fast), glycolysis (medium speed), and the oxidative system (slower, for longer activity) [9]. The phosphagen system relies on phosphocreatine to quickly restore ATP, which is why creatine is so important for short, high-intensity efforts like sprints, heavy lifts, and explosive CrossFit movements.

Your body makes some creatine (about 1g/ day) naturally in the kidneys, liver, and pancreas from amino acids, and you can get a small amount from foods like red meat and fish (~1–2 g per pound). [10] But to reach the optimal 5 g per day, you’d need to eat roughly 2.5 pounds of steak every day—not very practical! That’s why supplementing with creatine monohydrate is recommended to consistently support strength, power, and workout intensity.

1) Creatine just causes water retention and bloating

Reality: Creatine increases intracellular water inside muscle cells (cell volumization), not subcutaneous water. This supports muscle growth and recovery, not “puffiness” or bloating. Studies seem to indicate that short term water retention can occur (several days) but is less common with long term use. [11] Meaning, it is possible you may experience water retention the first few days of using creatine but then your body is likely to return to baseline water retention.

2) You need a loading phase to see results

Reality: Loading (20 g/day for 5–7 days) saturates muscles faster, but consistent daily dosing of 3–5 g/day achieves the same saturation in ~3–4 weeks without the GI upset from loading. [11]

3) Creatine is only for bodybuilders

Reality: Creatine benefits all athletes, including CrossFitters, runners, and older adults. It improves strength, power, recovery, and even cognitive function. [12]

4) Creatine is bad for your kidneys or liver

Reality: Research shows long-term creatine use is safe in healthy individuals when taken at recommended doses. Issues only arise in people with pre-existing kidney disease. [14]

5) Creatine is a steroid

Reality: Creatine is not a hormone; it’s a naturally occurring compound in meat and fish that helps regenerate cellular energy (ATP).

Protein is crucial for muscle repair and adaptation. While most athletes should aim for 0.7–1.0 g per pound of bodyweight daily, it can be hard to hit those numbers with food alone. Daily schedules, busy lifestyles, and limited meal prep time often make it challenging to consume enough high-quality protein consistently. This is where supplemental protein, like shakes or powders, can be convenient to help meet your daily needs. However, they should be viewed as a supplement to whole foods, not a replacement for balanced meals, which provide additional nutrients, fiber, and healthy fats essential for overall health and performance.

Supplements can’t replace hard work, rest, and real food—but they can give you an edge. For CrossFit athletes, magnesium, creatine, and protein powder are evidence-based tools to support recovery, strength, and performance.

Build the foundation with whole foods—then use supplements strategically to fuel not just workouts, but long-term health.

[1] Kaur, J., Khare, S., Sizar, O., & Givler, A. (2025, February 15). Vitamin D deficiency. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK532266/

[2] Ankar, A., & Kumar, A. (2024, September 10). Vitamin B12 deficiency. In StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441923/

[3] Dighriri, I. M., Alsubaie, A. M., Hakami, F. M., Hamithi, D. M., Alshekh, M. M., Khobrani, F. A., Dalak, F. E., Hakami, A. A., Alsueaadi, E. H., Alsaawi, L. S., Alshammari, S. F., Alqahtani, A. S., Alawi, I. A., Aljuaid, A. A., & Tawhari, M. Q. (2022, October 9). Effects of Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids on Brain Functions: A Systematic Review. Cureus, 14(10), Article e30091. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.30091

[4] U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements. (2016, February 11). Magnesium — Fact sheet for health professionals. Retrieved [Access Date], from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Magnesium-HealthProfessional/

[5] Volpe, S. L. (2013, May 1). Magnesium in disease prevention and overall health. Advances in Nutrition, 4(3), 378S–383S. https://doi.org/10.3945/an.112.003483

[6] Breus, M. J., Hooper, S., Lynch, T., & Hausenblas, H. A. (2024, July 26). Effectiveness of magnesium supplementation on sleep quality and mood for adults with poor sleep quality: A randomized double-blind placebo-controlled crossover pilot trial. Medical Research Archives, 12(7). https://doi.org/10.18103/mra.v12i7.5410

[7] Tarsitano, M. G., Quinzi, F., Folino, K., Greco, F., Oranges, F. P., Cerulli, C., & Emerenziani, G. P. (2024, July 5). Effects of magnesium supplementation on muscle soreness in different type of physical activities: A systematic review. Journal of Translational Medicine, 22, Article 629. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12967-024-05434-x

[8] Guimarães-Ferreira, L. (2014, January–March). Role of the phosphocreatine system on energetic homeostasis in skeletal and cardiac muscles. Einstein (São Paulo, Brazil), 12(1), 126–131. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1679-45082014rb2741

[9] Haff, G. G., & Triplett, N. T. (Eds.). (2016). Essentials of strength training and conditioning (4th ed.). Human Kinetics.

[10] Cooper, R., Naclerio, F., Allgrove, J., & Jimenez, A. (2012, July 20). Creatine supplementation with specific view to exercise/sports performance: An update. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 9(1), Article 33. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-9-33

[11] Antonio, J., Candow, D. G., Forbes, S. C., Gualano, B., Jagim, A. R., Kreider, R. B., Rawson, E. S., Smith-Ryan, A. E., VanDusseldorp, T. A., Willoughby, D. S., & Ziegenfuss, T. N. (2021, February 8). Common questions and misconceptions about creatine supplementation: What does the scientific evidence really show? Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 18, Article 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-021-00412-w

[12] Xu, C., Bi, S., Zhang, W., & Luo, L. (2024). The effects of creatine supplementation on cognitive function in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Nutrition, 11, Article 1424972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2024.1424972

[13] Kreider, R. B., Kalman, D. S., Antonio, J., Ziegenfuss, T. N., Wildman, R., Collins, R., Candow, D. G., Kleiner, S. M., Almada, A. L., Lopez, H. L., & others. (2017). International Society of Sports Nutrition position stand: Safety and efficacy of creatine supplementation in exercise, sport, and medicine. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 14, Article 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12970-017-0173-z

[14] Brose, A., Parise, G., & Tarnopolsky, M. A. (2015). Effect of creatine supplementation during resistance training on lean tissue mass and muscular strength in older adults. Open Access Journal of Sports Medicine, 6, 267–275. https://doi.org/10.2147/OAJSM.S123529

[15] Schoenfeld, B. J., Aragon, A. A., & Krieger, J. W. (2013). The effect of protein timing on muscle strength and hypertrophy: A meta-analysis. Journal of the International Society of Sports Nutrition, 10, Article 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/1550-2783-10-53